Retention is a measure of how often someone comes back and uses your app after they first sign up.

Here is a quick framework to measure and improve user retention. I’ve distilled everything I know about improving retention into 9 YES/NO questions.

Go through the questions below and score your product by answering the yes/no questions. For the ones you answer no to, the sections below will explain how to think about improving that aspect of your product.

- Does your product make a clear promise?

- Do you know how often people have the problem you help them solve?

- Do you know what your product’s core action is?

- How many people continue to use your product six months after they sign up?

- Have you segmented your retention curve by the different types of users in your app?

- Do you know where the single biggest dropoff is in your current onboarding experience?

- Have you mapped out the number of times each person performed your core action last month?

- Have you spoken to five of your most and least engaged users?

- Do you know why people say they leave?

This audit is meant for software-as-a-service products that have already found product-market fit. The principles still apply but it’s not great for early-stage startups, e-commerce products or attentional products like social platforms.

Ideally, you’ll have been in business for a year or two. Focusing on retention makes the offers the best return on investment once you have about a thousand new users a month. If you’re way past this stage then you’re probably already doing all of this stuff.

Does your product make a clear promise?

You want to be clear about the problem your product was designed to help people solve.

A narrow, specific promise is easier to deliver on. It sets clear expectations and leaves very little wiggle room for misunderstandings.

A broad, vague promise just leaves the door wide open to a mediocre product experience. The wrong people show up with the wrong expectations and everyone is disappointed.

You might have one of those products that solves lots of problems for different people. That’s fine, just pick your primary use case and let’s focus on that for now. You can repeat the process with all your other use cases later.

A clear, narrow promise is much easier to remember.

The problem your product was designed to solve acts as an organic trigger that reminds people about your product.

If they know your product helps them deal with X there’s a chance they’re going to think of you the next time they have to deal with X.

Do a good job of solving the problem the first time they use it and people will remember you the next time they have the problem. Help them solve the problem a second time and you’re well on your way to building a product habit.

Let’s not get carried away though, it all starts with a clear problem.

Improving retention boils down to delivering on the promise your product makes.

The narrow and more specific you promise is the easier it is to deliver on.

Do you know how often people have the problem you help them solve?

A product is meant to help someone solve a problem.

Understanding when your problem occurs lays the foundation for how often people are expected to use your product.

If people deal with your problem once a month, sending them emails every day is going to feel like spam. On the other hand, a monthly reminder is will probably be appreciated.

The natural frequency of the problem your product solves is the bar you use to gauge what’s too little and what’s too much.

Establishing this frequency isn’t an exact science, you’re going to have to ballpark it.

You could always look at how often people use your product and extrapolate from there. The problem with this approach is that people might be using it less than they should.

“Most of my users log in twice a month”. Twice a month, that’s the bar. If your product is designed for a problem people have two or three times a week then you’ve got loads of work to do.

It’s easier to benchmark usage with your best guess of how often your problem naturally occurs.

You can refine this measurement by thinking about other ways people solve the problem. How do people who don’t use your product solve the same problem? How often do they have to deal with the issue?

I’ll close this up by saying that you might have lots of different use cases. Some people use your product to set things up once a month, other people use it to sort stuff two or three times a week.

Pick your primary use case and focus on that for now. Then repeat the process for all your other use cases later.

Do you know what your product’s core action is?

Your core action is the thing people do in your product to deal with the problem they signed up to solve.

You want to start by shortlisting all the things people can do in your app to address their core motivation for signing up.

To narrow it down, think about how often people experience the problem they’re dealing with. If the problem is filing your taxes, there’s not a lot you can track on a monthly basis that will tell you if people are successfully using your product to file their taxes this year. A yearly metric makes more sense here.

Airbnb use yearly metrics. People only go on holiday one or twice a year so it makes sense to track how many people book nights each year.

On the other hand, a chat app like WhatsApp helps people coordinate on a daily basis. Tracking how many people send messages each day gives you a clearer picture of how useful it is.

A good core action will line up with how often the problem naturally occurs.

If you have data to run a correlation then the last step is to correlate your contending actions with long-term usage. The whole point of a core action is that when people do it they’re more likely to continue using your product in the long run.

If you still have options after you’ve run your correlations then always go with the metric that’s easiest to understand. A good metric that’s simple to grasp is better than something more accurate with lots of footnotes.

How many people continue to use your product six months after they sign up?

Before you can begin measuring the number of people who use your app you have to define what “using your app” means. Meaningful usage implies that people are using your product to solve the problem they signed up to deal with.

Meaningful usage for Airbnb would be booking a night. For WhatsApp, it’s sending a message. If your app does rideshare then it’s probably booking a cab. If you deliver food then it’s likely ordering dinner.

Once you have your core action then you need to figure out your usage interval. Your usage interval is based on how often the problem you solve naturally occurs.

If Airbnb looked at how many people booked nights a week, it might look like nobody uses their app more than once. People go on holiday once, maybe twice a year. It makes more sense to look at how many people book nights a year. What looked like lots of inactive users, now looks like lots of repeat business.

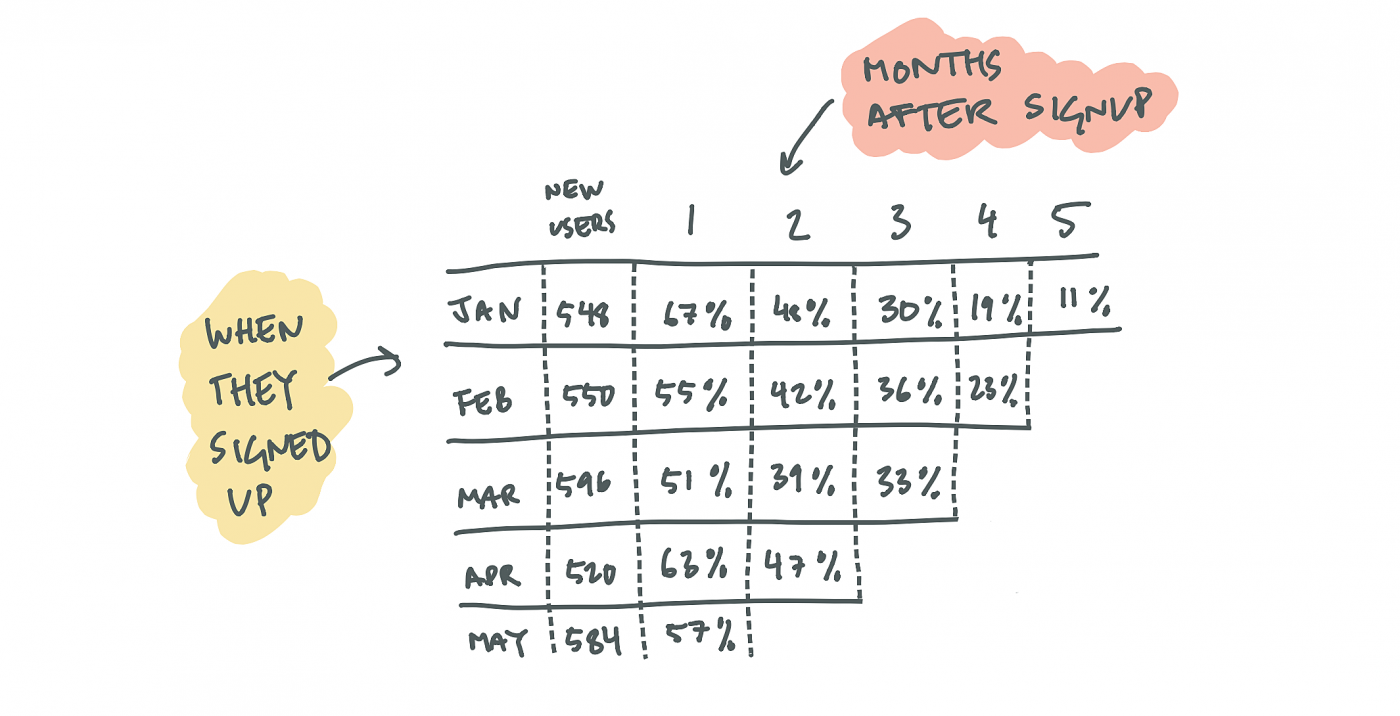

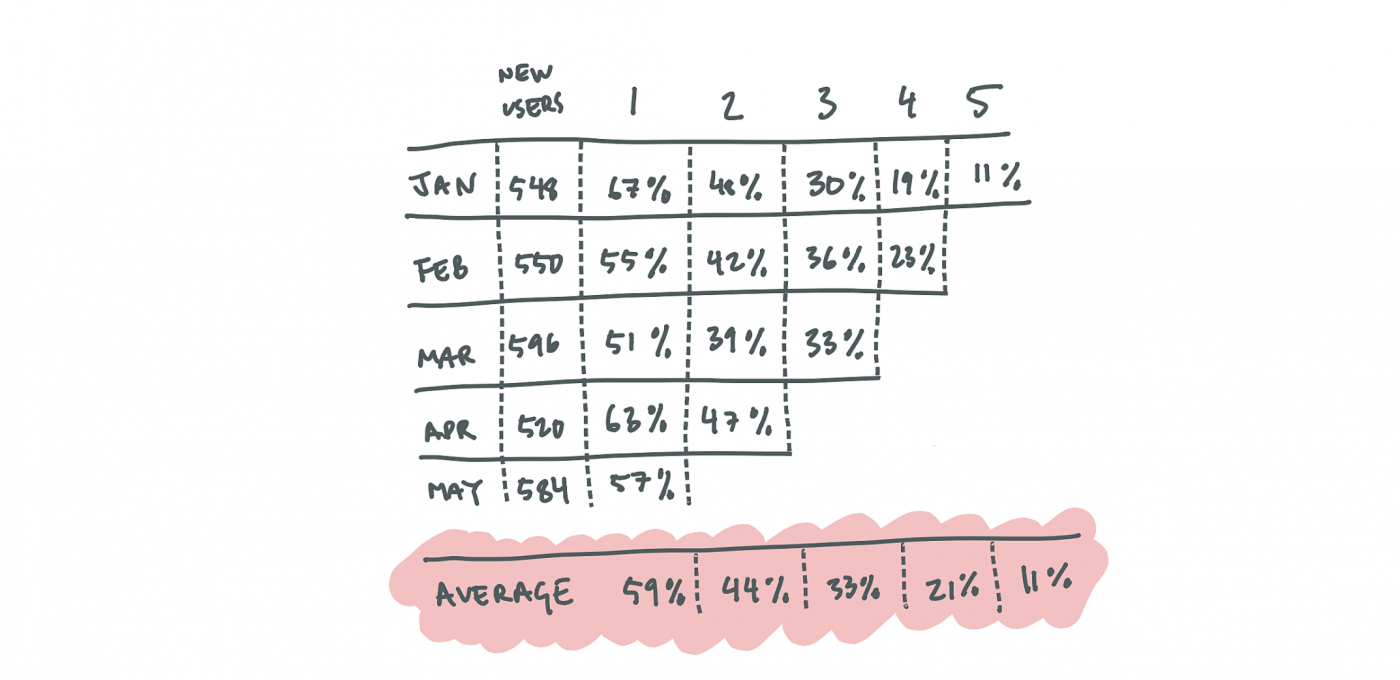

Once you have your core action and your usage interval you can construct a cohort chart.

The first column in a cohort chart corresponds to your usage interval. If your usage interval is monthly then it groups people by the month they signed up. The rows show you what percentage of people continue to perform the core action each month after they signed up.

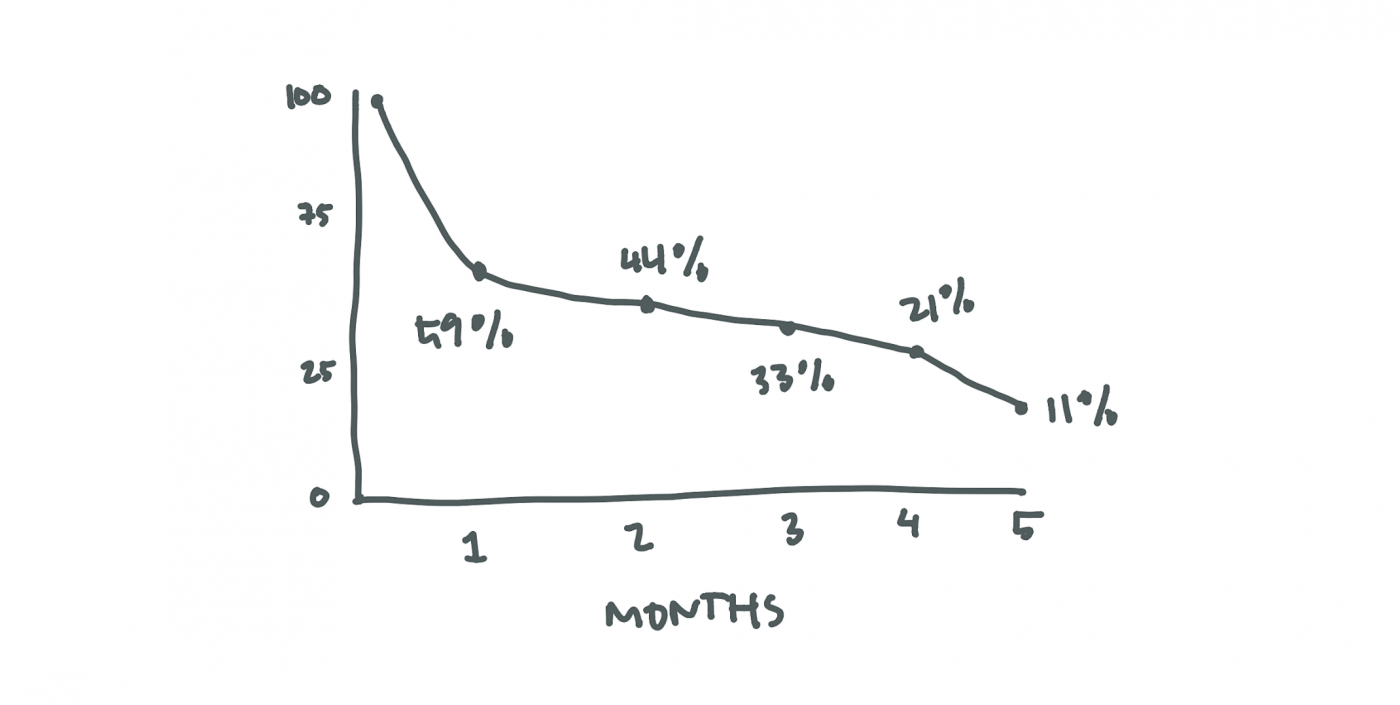

Then average out all the columns out and plot them on a curve.

Now you know how to work out the exact percentage of people than continue to use your product 6 months weeks after they sign up.

Have you segmented your retention curve by the different types of users in your app?

If you’ve plotted a retention curve and you know how many people continue to use your product six months after they sign up then the next step is segmentation.

Segmentation means looking at subsets of different types of users. Let’s say, on average 40% of people who signup continue to use your product six months later. If you break it down you might discover that 60% of people who sign up with a business email address continue to use the product. On the other hand, only 20% of people who use a free email account (like Gmail) stick around.

You can use this information to focus on your strengths and cut your losses. “We now require everyone to have a business email to sign up”.

The other way to look at this is to focus on improving the segments that pull your average down. Segmentation reveals where you’re underperforming. It maps out regions of fertile ground for growth.

The easiest way to start segmenting a retention curve is to use the data your tools automatically track. What technology people use, their general location, which landing page they came through, the traffic source they came from, etc.

Segmentation gets more interesting once you start to look at more specific user-generated inputs. The free vs paid email is one example here. The actions people take in their first two weeks is another, the notifications they respond to, the ones they ignore, how often they interact with customer support, the features they use, the one’s they don’t, how often they use the product, their payment tier, etc.

The idea is to segment your curve in as many ways as you can. Each layer of segmentation tells a different story.

Do you know where the single biggest drop-off is in your current onboarding experience?

Onboarding is a murky term. Sometimes people mean your first session with a product. Other times it refers to those popups and guided welcome tours I have to endure. Other people think of onboarding as the initial two weeks with a product, usually the free trial territory of the experience.

I like to define onboarding as everything that precedes someone successfully building a habit around a product.

I’m defining ‘building a habit’ as doing a specific action a set number of times withing a specific timeframe.

I’m not pulling this ‘set numbers of times’ out of a 🎩. I have to sit down with the data and figure out how many times people have to perform your core action within an initial timeframe to stand a chance of becoming a long term user.

The only way I know how to do this is to run correlations between how many times people perform an action within different timeframes and how likely they are to continue using your product six months later.

Once I have a placeholder for what people need to do to stand a chance of building a long term habit around a product I have an endpoint to work with.

The idea here is to start at the endpoint and then work backwards. I map out all of the touchpoint people must go through till I get to when they first signed up.

Then I can measure exactly how many people made it to each touch point. Mapping the onboarding experience in this way lets me highlight the single biggest dropoff in the journey people take to build a habit with a product.

Visualising the onboarding experience as a funnel and measuring where the most significant drop-offs are is one way I’ve found high impact opportunities for growth.

Have you mapped out the number of times each person performed your core action last month?

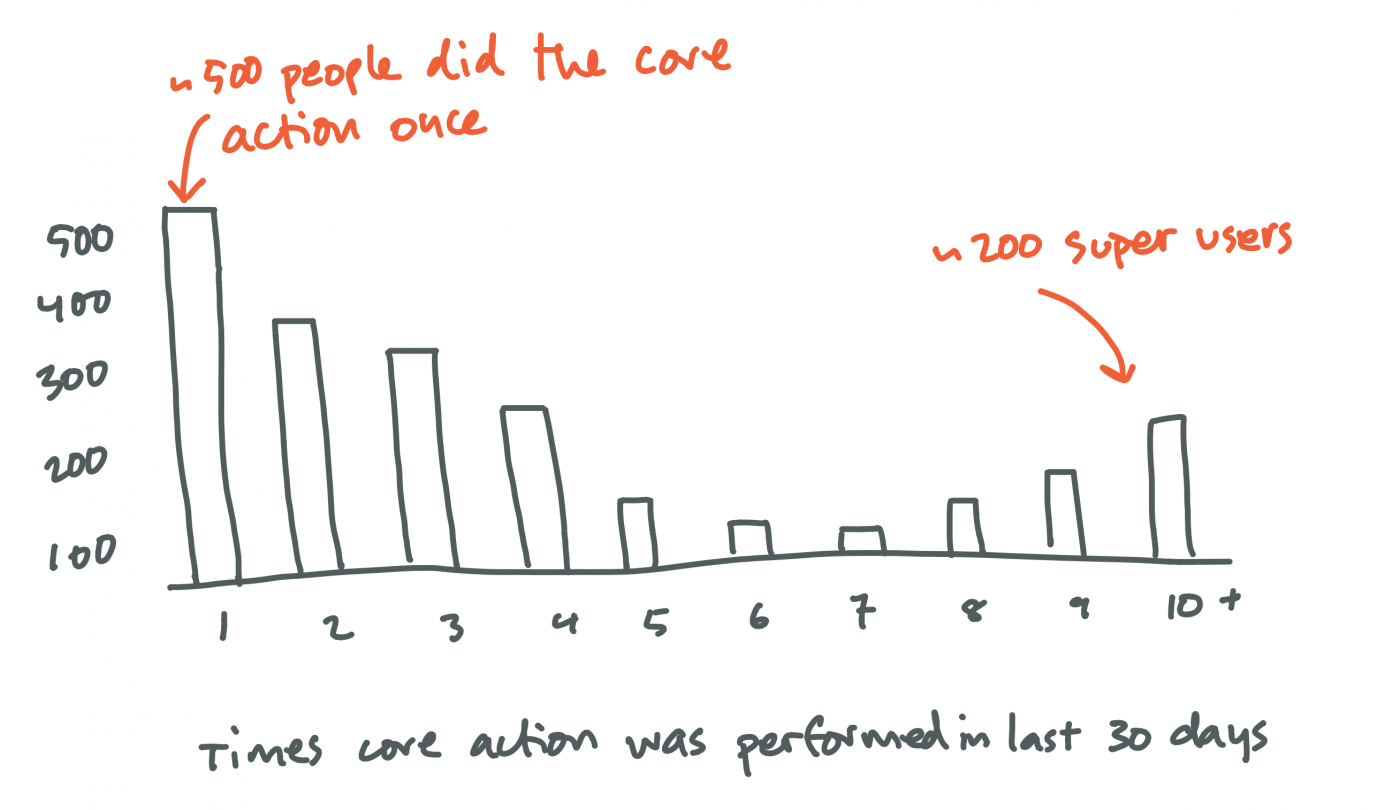

When I begin working with a product my primary focus is to understand how the core value proposition translates to specific actions in the product. I try and map out all the steps that lead to people becoming a habitual user. Once this initial phase of work is complete the next step is to figure out who the super users are.

One way I find super users is to figure out who performs you core action the most.If I have done my job well then the core action is the best proxy we have for people succeeding with your product. It stands to reason that the people who do it the most are getting the most out of the product.

I’ll take any given month and look at the number of times each person performed the core action. This gives me a spectrum of usage. I also make to remove people who just signed up so that I don’t distort the data.

What I’m trying to understand is the differences in the way that people on either end of this spectrum think about and use the product.

The best way I know how to do this is to speak to people and listen to how they talk about using product.

Speaking to 5-6 people from each group is usually enough to get a sense of the key points of contrast in how each groups thinks about the product. These key point of contrasts, or use cases, serve as goal posts that I can then use to encourage the least engaged group to head towards.

How can you help more people think about your product as your super users do?

Have you spoken to five of your most and least engaged users?

A good interview lasts about 15 minutes. I schedule half an hour just in case but I don’t ask for more than 15 minutes.

“Can you tell me about how you first started using (the product)?“

This is one of my favourite opening questions. It gets straight to the heart of why they use the product but still conversational and warm.

If needed I will clarify that I am asking why they started using it not how they discovered the product, but the loose phrasing here usually encourages people to respond with a story rather than bullet points.

“Tell me about the last time you (used the product)?”

Once people establish their initial motivation for using the product then I try and understand if their current usage lines up with their initial motivation or how it has changed.

When needed, I have follow-up questions to help move the conversation towards the insight I am looking for.

- What were you trying to accomplish?

- Can you take me through what you did?

- What was the context at the time?

- What were you doing before that?

- Why were you trying to achieve this?

I try not to ask these question when possible. Undirected, people are more likely to take the conversation to a place that matters.

I like to end conversations with:

“Is there anything else I should have asked?”

This is a great question because sometimes people understand what you’re trying to do but you haven’t given them an opening to say what they want to say. Other times you can sense that the conversation isn’t over yet and it’s because they have questions. Worst case scenario, they say no.

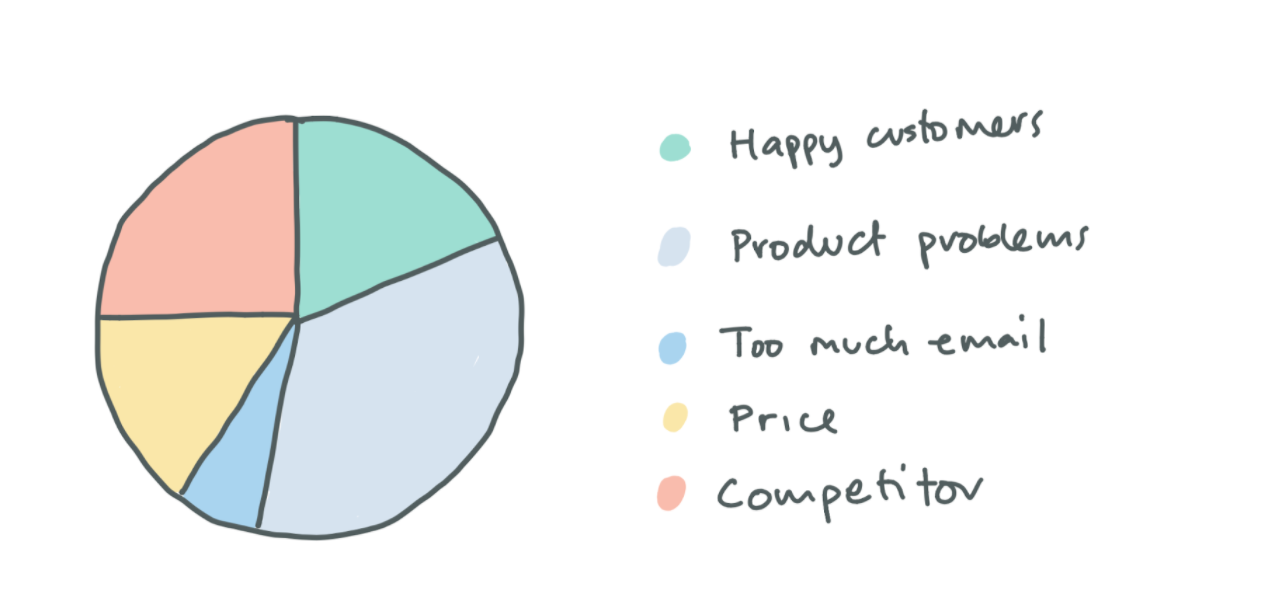

Do you know why people say they leave?

When people stop using a product it’s important that I understand if it’s because they couldn’t use the product, if they didn’t like it, or if I’m dealing with happy churn.

One way to gather this data is to survey people when you cancel their account. The trouble with exit surveys is they don’t account for people who can’t use your app for whatever reason. There’s also little to no chance of changing someone’s mind once they have decided to cancel.

I’ve found that it’s better to sending out an email after people stop performing the core action for a period of time. They’re still using the app so they’re more likely to respond, but they’re heading out the door so it’s important to understand why. Don’t send it too soon because you will just spam people on holiday. However, leave it too late and you probably won’t get a response.

You want to know if there is a predominant reason people leave so that you can do something about it.

In most cases, you already have a decent sense of why people leave. Feedback is more confirmatory than anything else. Gather your teams best guesses and send them to people as a multiple-choice questionnaire.

It typically boils down to your thing not working, you sending them too much spam, it being too expensive or them finding something better.

If people leave because they couldn’t use your app, then you have an engineering problem. You should have alerts and error logs that show you this well before people start leaving. Sending emails to this group is your last line of defence. You should be able to detect problems like this well before they are ready to leave.

Further learning resources…

I often get asked how I learned about user retention and what resources are available to learn more about retaining customers.

I’ve put together the following reading list to help expand your understanding of how to retain customers. This list is not exhaustive, I’ve limited the recommendations to the most useful ones I’ve found so far.

Amplitude’s playbook on mastering retention

This is the first resource on how to retain customers that I discovered and completely fell in love with. It’s an excellent introduction to the topic. The book is practical. As a result, it shows you how to define your core action and set up your analytics instrumentation so that you can build a retention curve. Moreover, it’s completely free.

Reforge’s retention + engagement deep dive 💰

This one’s not free. However, it is the single most comprehensive resources on how to retain customers I have ever come across. We no longer have one-off courses but an annual membership. You’re a member, but you can read the details here around pricing and what’s included. The program is fairly hard to get into. You must have a few years of experience in the industry to apply. Above all, you must also be working on a product team when you apply. If you don’t meet these criteria, the course will be an expensive waste of time. If you meet the criteria, there’s nothing else quite like it. I am grateful to have been part of this program.

Udacity’s course on activation and retention strategy 💰

This program is jam-packed with useful information. It’s an excellent next step if you’ve read the Amplitude playbook and want more.

The elements of user onboarding💰

This one is not specifically about how to retain customers. However, a large part of retention comes down to improving your onboarding experience. I have the utmost respect for Samuel’s work and perspective, and his book comes highly recommended. If you want to improve how you think about your onboarding experience look no further. Sign up for my free workshop and you’ll also get a link that gives you 20% off the book.

What is good retention by Lenny Rachitsky

As soon as you start working on retention, you will begin to ask yourself what good retention mean. I will point you to Lenny’s Benchmarks here. I continuously go back to this reference when I want to know what good retention means for products in different industries.

Brian Balfour on how to retain customers

I will leave you with Balfour’s talk on retention at CXL from 2016. I’m sure he has done even better presentations on the topic since. This video is where I first discovered his work and it remains my favourite.

There you have it, my top resources and advice on on how to retain customers 👍

If you know any other resources that you think should be on the list please let me know.

More useful links to improve your user retention…

- Everything I know about constructing a value proposition and putting a bitchin’ landing page together.

- A landing page teardown in 20 questions

- Some useful benchmark for retention in different industries

- Segment your data by user intent

- The Power User Curve: The best way to understand your most engaged users by Li Jin

- The Power User Trap by Reforge

- How to find people to speak to

- A little game I play to score my interviews

- Rob Fitzpatrick on interviewing people who are already using your product